|

| Habronattus pyrrithrix male (Photo: Ian M. Wright) |

Jumping spiders make up the largest family of spiders. Constituting the family Salticidae, this family contains over 600 described genera and over 6000 described species as of 2019. With a family this big, this means jumping spiders show a lot of diversity, and live just about everywhere with the exception of polar regions.

These spiders earn their name because of their agility in jumping. When they're ready to jump, the spiders elicit a change in what is called “hemolymph pressure,” basically their equivalent of blood pressure. They do this by contracting muscles in the upper region of their bodies, forcing blood to their legs, causing their legs to extend rapidly. This sudden extension of their legs is what propels them. They also can spin a line of silk as they jump which acts as something of a dragline. A 2013 paper published in the Royal Society journal Interface looked at the differences between a jumping spider that does create a silk dragline and one that doesn’t. You can see difference in how they land in this video: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=37&v=NiotoNfcq9g&feature=emb_title)

|

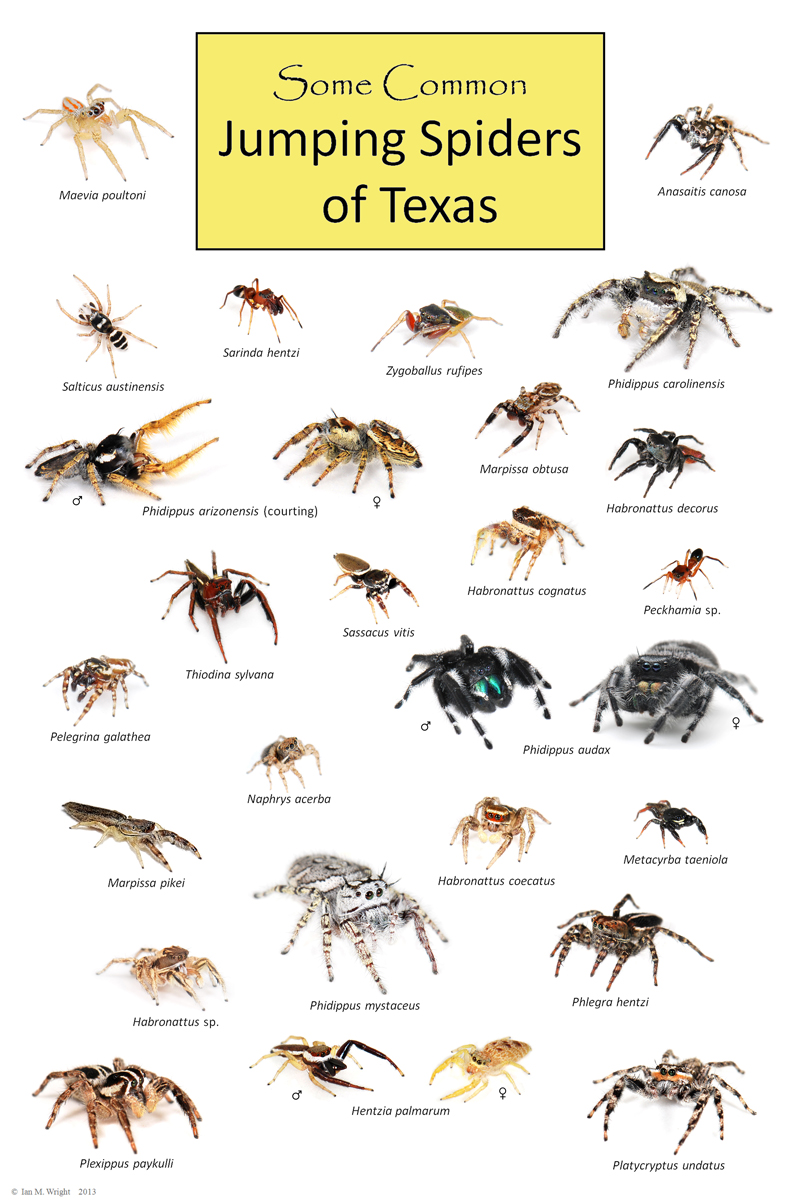

| Chart courtesy Ian M. Wright. View larger version here. |

Their eye pattern is the clearest single identifying characteristic. They have four pairs of eyes. The front four are the ones that help most with species identification. There are three secondary pairs that are fixed and a principal pair that can move. Among arthropods, these spiders have some of the best vision. Their vision system is quite sophisticated, allowing them to see a great amount of detail.

These spiders also can “hear” quite well, but not through ears like we have. They hear through sensory hairs on their bodies that send signals to their brains. They can sense vibrations from ten feet away, which is quite a distance for a tiny insect.

Jumping spiders do not build webs to catch their meals, but jump on their prey, usually small insects, and inject them with venom. Their venom poses no threat to humans! Jumping spiders learn from encounters with prey, so that their hunting skills grow as they age.

Juvenile jumping spiders are difficult to identify. This is because their colors and secondary sex characteristics are not yet developed.

What are some species you can spot here in Central Texas? The handy chart above shows quite a few, and here are some interesting details about some of the genera.

Habronattus are a genus of ground-dwelling jumping spiders, sometimes called “paradise spiders.” They get their common name from the fact that the female is rather plain looking compared to the very showy male, much like the Birds of Paradise.

Phidippus are the US’s largest jumping spiders and include the most recognized species. In Central Texas, Phidippus arizonensis are one of the most common jumping spiders and are probably the most common Phidippus in the area.

Salticus are usually marked with a white and black pattern, which has earned them the nickname of “zebra spiders.”

Sarinda and Peckhamia are genera of ant-mimicking jumping spiders. In general, spiders are actually the most common ant mimics. This is called myrmecomorphy. They do this for a number of reasons, from needing to deter predators that don’t like ants, to needing to deceive other ants into thinking it is one of them. Take a look at a Peckhamia here (https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=25&v=2Pgs_-Lckno&feature=emb_title)

Marpissa This genus is well-known for having short bodies and a large set of eyes. They build web tents where they will wait for prey to pass. They will then stalk their prey and jump on it when close enough. They are also known to steal prey from webs of spiders as well.

Special thanks to Ian M. Wright, Research Associate at the University of California - Riverside, for his assistance with this article. You can follow him on Twitter (@ianmwright86) as well as Instagram (handles ianmwright86 and tinyspheres). To see more of his insect photography, visit this link.

DID YOU KNOWMales dance and “sing” for the females during courtship, the song consisting of clicks, ground tapping, and buzzing. That male better impress the female, because sometimes if she’s not into him, she will eat him. Researchers often study jumping spiders’ jumps as a way to improve the jumping abilities of robots. In fact, researchers at the University of Manchester trained a regal jumping spider to leap on command in order to study her jumps. This spider was named “Kim.” Check out video footage of her jumps here. |

SOURCES

Chen Yung-Kang, Liao Chen-Pan, Tsai Feng-Yueh and Chi Kai-Jung. “More than a safety line: jump stabilizing silk of salticids.” J.R. Soc. Interface. 10: 20130572 (accessed online: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/full/10.1098/rsif.2013.0572)

“Habronattus jumping spiders,” Featured Creatures, Entomology & Nematology, University of Florida (accessed online: http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/MISC/Habronattus_jumping_spiders.htm)

Kirkpatrick, Noel. “10 Wild and Crazy Facts About Jumping Spiders” Treehugger, May 5, 2020 (https://www.treehugger.com/jumping-spider-facts-4864103)

Price, Michael. “WILD ABOUT TEXAS: Bold jumping spider has an almost humanoid look.” Odessa American, October 8, 2011.

Sana, Suri. “Spiders Disguise Themselves as Ants to Hide and Hunt Their Prey.” IFL Science. (accessed online: https://www.iflscience.com/plants-and-animals/spiders-disguise-themselves-ants-hide-and-hunt-their-prey/)

Thompson, Gina. “Marpissa formosa” Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology (accessed online: https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Marpissa_formosa/)