Photo: Henrik Ishihara Globaljuggler (Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

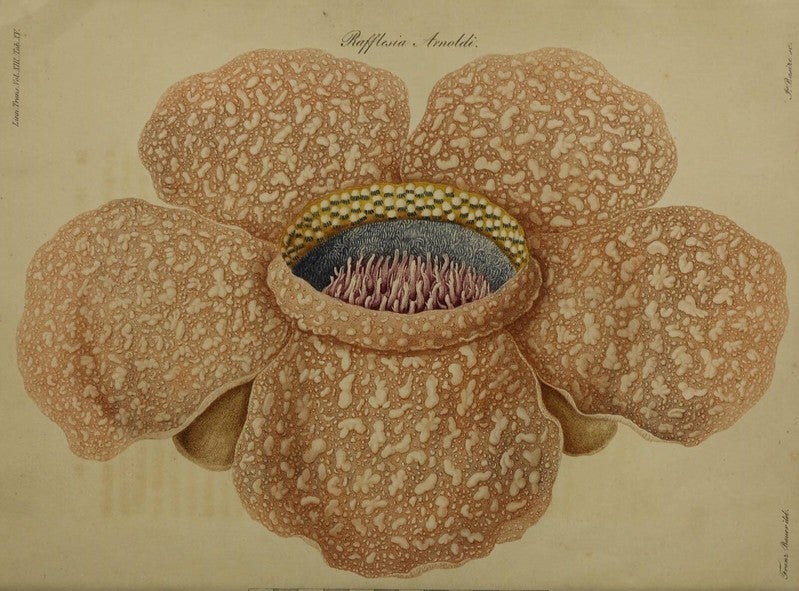

Next in our parasitism series is the flowering plant in the parasitic genus Rafflesia, also known by the evocative names of the “corpse lily” or “carrion flower.” Why does it deserve our attention in the Halloween series? Because it ticks off many check boxes for gross and creepy things.

IT’S STINKY

The flower smells like rotting flesh. Well, to us anyway. The scent is actually really attractive to carrion flies who can’t seem to get enough of it as they pollinate away.

IT’S STEALTHY

Undetected by the host plant, Rafflesia parasitizes Tetrastigma, a woody vine in the grape family. It accesses the vine through an organ called the haustorium and drinks up water and nutrients. Rafflesia also barely noticeable on its host. That is, until it’s time to flower, then the show starts. The buds will appear suddenly, grow for months, then bloom into something that seems from out of this world. The blooming period itself is over quite quickly in about eight days after which it will create a smooth-skinned fruit.

IT’S GOOEY

The powdery yellow pollen we are accustomed to with many flowers is not the case with this plant. Dr. Charles Davis, Harvard professor of organismic and evolutionary biology, explains that the pollen is “produced as a massive quantity of viscous fluid, sort of like snot.” The pollinating flies will get a bit of this on their backs where it dries and remains viable for a while.

IT’S A MONSTER

The members of this genus produce huge flowers. Rafflesia arnoldii, found in the Sumatran Montane Rainforests ecoregion, makes the world’s largest bloom. The smallest flowers still end up being the size of a dinner plate, but the smell might make you think twice about eating from it. (Of note, however, the flower is considered a delicacy in Thailand.)

IT’S WEIRD

Just when you thought it couldn’t get any stranger, there are more quirks about this plant.

Rafflesia flowers generate heat. This is called thermogenesis, and it creates a nice environment for pollinators to do their thing without expending much energy.

But perhaps the strangest thing about this plant is that it does not photosynthesize, meaning it does not convert sunlight into chemical energy as most plants do. It actually has no chloroplast genes. When Dr. Charles Davis sequenced the genes, he discovered that Rafflesia were part of the order of Malpighiales, but the genes also put them into the order of their host plants, Vitales, which had been considered before to be extremely unusual. Basically, this is an example of a gene transfer without sex.

Read all of our All Things Creepy Halloween blogs!

Part 1: mermithids and earwigs

Part 3: the tongue biters

Part 4: mite pockets

Part 5: crypt keepers

1821 illustration from Biodiversity Heritage Library.

SOURCES

Sargent, Channing “Species of the Week: Rafflesia” One Earth. October 5, 2021. (https://www.oneearth.org/species-of-the-week-rafflesia/)

Shaw, Jonathan “Colossal Blossom: Pursuing the peculiar genetics of a parasitic plant” March-April, 2017. Harvard Magazine (https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2017/03/colossal-blossom)