Pigeons are so ubiquitous, searching our sidewalks and streets for anything edible, perched overhead on powerlines and building ledges, we don’t really give them much thought. In fact, pigeons get a pretty bad rap sometimes, are written off as nothing more than “rats with wings.” However, they are, like many of our urban wildlife neighbors, interesting creatures that deserve some attention.

Common pigeons (Columba livia) are members of the bird family, Columbidae, which consists of doves and pigeons. They go by a few different common names: rock dove, rock pigeon, and of course just pigeon. Wild rock doves are pale grey with two black bars on their wings, but the feral or domestic pigeon, the ones we see strutting about on campus, vary in color and patterns, and males and females have few physical differences.

Why do they do these birds thrive in cities? In the wild, pigeons roost on cliffs, often along coastlines. So, our buildings and overpasses are perfect substitutes for these places in nature. Additionally, pigeons are granivorous, meaning their diet usually consists of grains, seeds, and fruits, but they are also very good at scavenging food waste in cities.

Breeding happens any time of the year, but the peak periods are spring and summer. Monogamous parents share incubation responsibilities, which last about 17-19 days. Nestlings are called “squabs.” Both parents feed them a “pigeon milk,” which is not milk at all, but a semi-solid produced in the bird’s crop, an expanded muscular pouch near the throat. Pigeon milk is yellow, resembles cottage cheese, and has a lot of fat, protein, and antibodies. The parents feed it to their young through regurgitation.

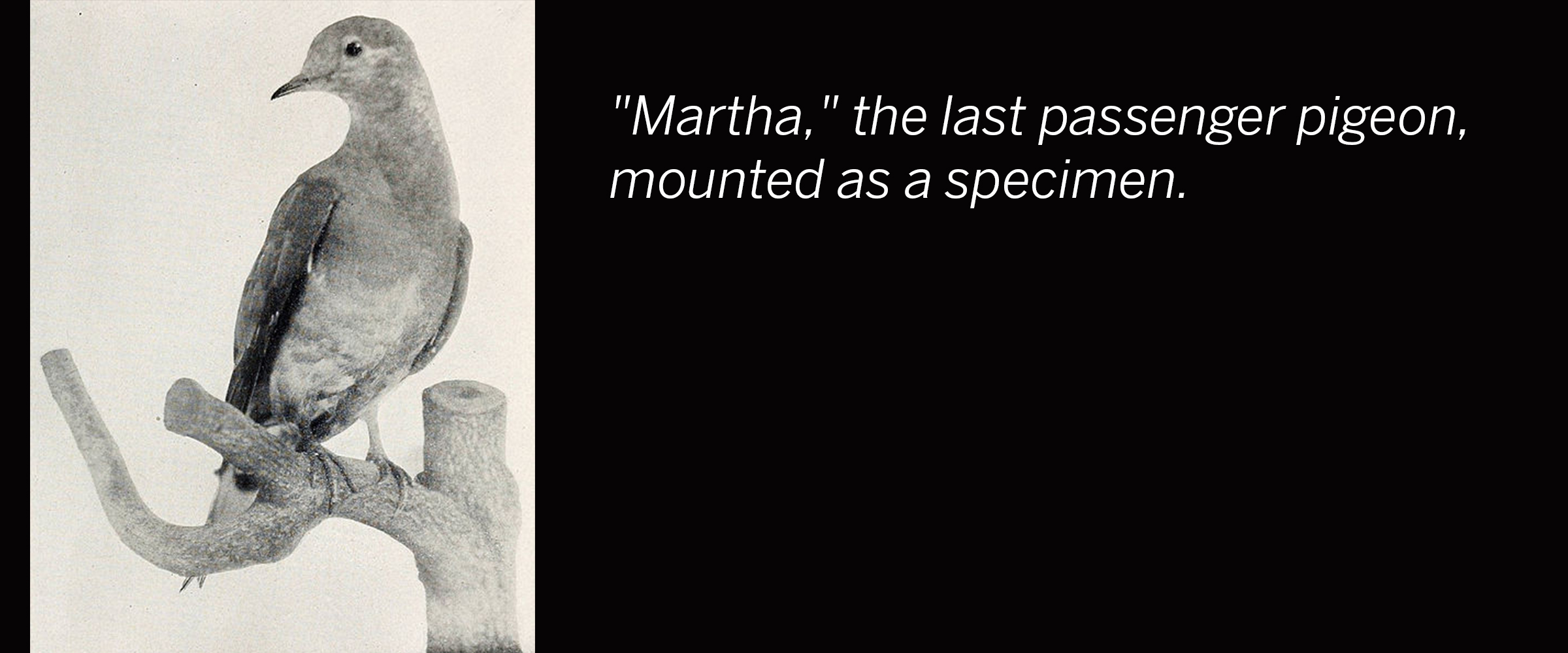

Pigeons live 3-5 years in the wild, but in captivity they can live for 15 years. The feral rock pigeon is considered invasive here, but were originally native to Eurasia and northern Africa. It’s thought they were introduced to North America in 1606 by French settlers, when the native passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) made up a quarter of the entire bird population in the US. Sadly, passenger pigeons are no longer with us, due in no small part to overhunting, habitat loss, and the fact that they did not lay many eggs per clutch. The last passenger pigeon, Martha, died in 1914. She is currently housed as a specimen in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. (Watch a video on her here.)

Pigeons have had a close relationship with humans for a long time, as messengers, food sources, and symbols. Bronze Age (2400-1500 BC) depictions of the bird have been discovered in Sumerian Mesopotamia. The birds can also be seen on Roman coins. People made pigeon offerings to Aphrodite, the Ancient Greek goddess of love, in exchange for blessings and favors. The bird, in the form as a white dove, also has a presence in Christianity, as just another of many examples.

As messengers, pigeons also have a long history. Records exist of their use in Ancient Greece and Rome. In the 14th Century, Englishman Sir John Mandeville wrote that pigeons were used to deliver messages in the Middle East during wartime. Ghenghis Khan used pigeons to relay messages to both allies and enemies. In both World War I and World War II, pigeons’ ability to deliver messages saved lives. One bird, Cher Ami, assisted in 1918 with the rescue of 194 stranded U.S. soldiers, all while his right leg was nearly shot off. GI Joe, another pigeon, saved over 100 Allied soldiers to deliver a message that halted a bombing. Both birds have recently been awarded medals for wartime bravery.

Because of their remarkable navigation skills, pigeons can not only deliver messages, but find their way back to their nests, even when they are up to 1300 miles away from them. It’s been mostly a mystery how they are able to do this, but recent research has led some scientists to believe that the earth’s magnetic field activates certain brain cells in the pigeon, like an internal compass.

Pigeon racing and breeding is an old hobby practiced in many parts of the world. During Victorian Era, breeding even had the enthusiasm of Charles Darwin, naturalist, geologist, and biologist. He owned a flock, belonged to pigeon clubs in London, and knew famous breeders at the time. His 1868 book, The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, has two chapters on pigeons.

The term “bird brain” need not apply to the pigeon. Research has shown them to share cognitive abilities usually associated with mammals’ more complex brains. In a 2017 Current Biology study, researchers showed that pigeons can discriminate abstract concepts of space and time, but use a different part of their brain to do so. In 1995, psychologists in Japan were also able to train lab pigeons to recognize and distinguish between paintings by cubist painter, Pablo Picasso, and impressionist painter, Claude Monet. Pigeons also have the ability to differentiate between strings of letters and actual words. They can also be trained with an 85% diagnostic accuracy to identify between benign and malignant biopsies of potential breast cancers.

Well, one might ask, how can these birds be so smart with all that head bobbing they do when they walk? Actually, this “bobbing” is really just a process of the bird moving its head forward, with the body to catch up shortly after. Pigeons do this to gain depth perception and stabilize their vision. The pigeon “walk” is such a distinctive characteristic of them, that even the muppet Bert of Sesame Street has a whole song and dance dedicated to it. If only all birds were so lucky!

DID YOU KNOW…

- Through DNA testing, we now know pigeons are closely related to the extinct dodo bird.

- The diet of Tower Girl, the resident Peregrine falcon here at UT, consists largely of pigeons. This is true for many other bird predators that live in urban environments. For urban Peregrines, pigeons make up around 80% of their diet.

- The term “rats with wings” was popularized by the 1980 Woody Allen movie Stardust Memories.

- Engineer and inventor Nikola Tesla supposedly had an affinity for pigeons and cared for injured ones from his hotel room in New York City. He had particular affection for a white female pigeon and was inconsolable upon her death.