The Stengl-Wyer Endowment supports year-long fellowships for doctoral candidates pursuing dissertation research in the area of Diversity of life and organisms in their natural environments. Recipients will receive a 12-month stipend of $34,000, full tuition and fees, staff health insurance, and an allowance of $2,000 to cover research and travel expenses.

The inaugural year of Stengl-Wyer Fellowships of 2020-2021 supports four fellows. Colin Morrison is the second of our Q&As with the fellows. His research seeks to answer questions about proximate mechanisms that contribute to the high levels of host plant specialization characterizing most herbivorous insects.

Tell us where you came from before UT, and what you studied then?

I was raised in Las Vegas, Nevada. I knew that I wanted to do something that would contribute to making the world better. Paying attention to the things in life that made me happy was a good place to start. Some of my favorite memories were exploring natural areas out of my element. I vividly remember a trip to Southern California when I went snorkeling and found myself surrounded by leopard sharks. They were so cool and mysterious! (Sharks remain my favorite animal!) These experiences motivated me to apply to college and learn how to get a job where I could get paid to spend time in places like these!

When I was finishing high school, I wasn’t sure about college. I applied to the University of Nevada Reno and was accepted, and right away had to choose a major. I figured I should be a biologist because biologists spend their time in nature, right? I really had no idea what I was in for, but I did know that I wanted to create a space for myself to be in nature. As I started learning about levels of organization from cells to ecosystems, I discovered this was a path that would keep me outdoors. I also realized that being a biologist would provide a chance to figure how complex biological processes give nature its complex character! This was a really important realization - being a grounded scientist is all about making personal discoveries while doing the work.

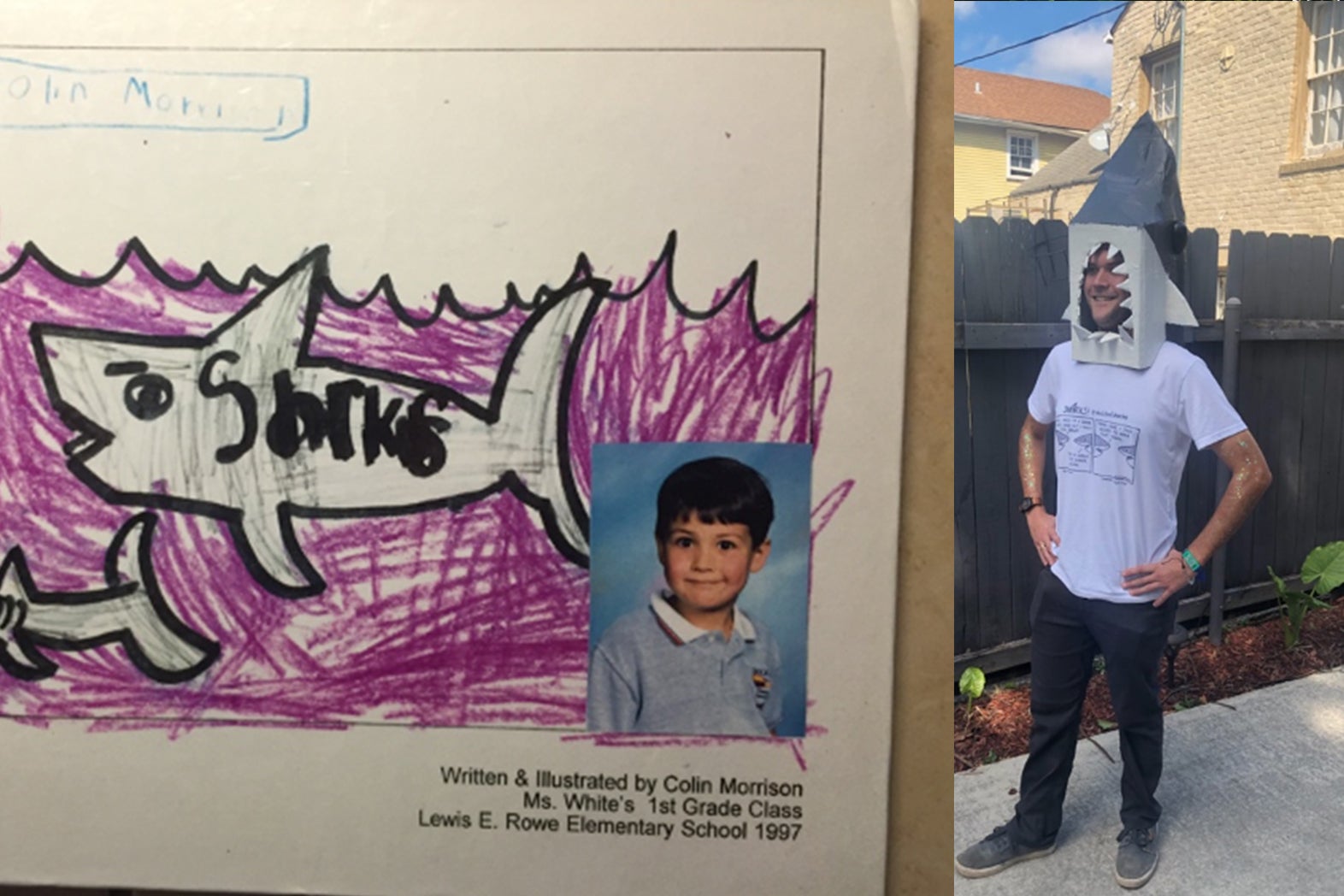

Left: Sharks by Colin in 1st grade. Right: Colin with shark helmet and shark comic t-shirt

In 2010, I got my first job doing question-based science. I earned a position as a National Science Foundation - Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) position working with Dr. Lee Dyer and his graduate student Andrea Glassmire at a wonderful research station in an Ecuadorian Cloud Forest (Yanayacu Biological Station and Center for Creative Studies). We studied how plant chemistry drives sympatric speciation among inch worm caterpillars and the wasps that parasitize them. This was a pivotal moment in my life. Our work was really integrative. The project mixed chemistry, field work, insects, statistics, friends, and adventure!

I continued working as a Research Assistant at the University of Nevada for five more years after. This led to fellowships with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (Massachusetts, USA) and the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (Gamboa, Panamá). My passion for research, discovery, travel and connection with people matured a lot during this period. All these experiences prepared me to begin working towards a PhD at UT Austin.

Clockwise from top left: Disonycha quinquelineata larva; female D. quinquelineata adult with freshly laid egg mass; Heliconius doris adult freshly emerged from the pupa; H. doris caterpillars feeding together on their host plant, Passiflora ambigua. Photo: Colin Morrison at La Selva Biological Station, Heredia Province, Costa Rica.

What got you interested in studying Heliconius caterpillars and passion vine flea beetles?

I have been involved in research that focused on the ecology and evolution of resource specialization for some time. This includes organisms like inch worms that eat plants in the black pepper family, tortoise beetles that consume morning glories, and cane toads eating huge quantities of the infamous bullet ants! While most of my previous research has been on chewing insects that coevolved to eat specific plants, I am interested in any ecological interactions associated with resource specialization from monkeys to microbes. The biological themes that underlie these kinds of interactions are variation in diet breadth and coevolution with chemicals present in the food source. To be a jack or all trades and a master of none? Or go all in on exploiting one resource extremely well? The truth is that most species of herbivorous insects specialize on eating a very small number of plant species out of the buffet of plants available in most environments.

Heliconius caterpillars and passion vine flea beetles are exemplar of coevolution on specific resources that are defended by suites of toxic chemical compounds. My advisor, Dr. Larry Gilbert, and his former students have studied Heliconius and passion vines for over 40 years. These researchers documented the natural history of this system extremely well. The importance of this cannot be overstated. Without this knowledge researchers that are new to the system (or any complex system) would be hard pressed to formulate good hypotheses to test. Field observations of the natural history operating around passion vines have given clues that Gilbert lab members have successfully leveraged in designing great experiments that characterized the processes governing the system. These include, pollen feeding and the evolution of big brains, pupal mating and conflicting selection pressure on male and female butterflies, warning coloration and the ability to sequester plant chemicals for defense, and repeatable evolution of mimicry complexes.

How do field labs like Brackenridge Field Lab and Stengl Lost Pines figure into your work?

Field stations are among the most significant institutions of scientific discovery on the planet. My career started at a field station and is largely maintained by ongoing work at several including Brackenridge Field Lab (BFL) and Stengl Lost Pines Biological Station (SLP). They have long-term data collection happening at the time scale required to make responsible conclusions about ecological processes that manifest over long periods of time. These long-term data sets are key to developing practical approaches to modern struggles.

I have gotten great value from using both BFL and SLP in multiple capacities. I have collected samples for my research, facilitated experiential learning in the field for students as a teaching assistant, the field stations are my favorite places to have productive meetings with colleagues, employees and potential collaborators, at BFL I get to share my passion and knowledge of nature with the public monthly during the grad student run outdoor lecture series Science Under the Stars, I use the first-class greenhouse facilities at BFL for running experiments and maintaining laboratory cultures of host plants and insects, and I regularly use the modern analytical lab in the BFL building for doing chemistry.

There is also something wonderful about field stations providing a way for people to get together, talk, share, and think about science as a community. The photo of me and my friends, fellow REU mentors, at La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica speaks volumes to that!

Does Texas present a unique situation, challenge or benefit for your research?

Texas presents me the opportunity to study local species of passion vine, passion vine specialized butterflies and flea beetles. The assemblages in Texas share both similarities and differences with those I study in Costa Rica. Texas passion vine-insect communities are diverse too; there are distinct communities of these plants and insects that have significant turn over in species composition from Central to South and East Texas. Early on in my program I recognized that I needed to expand my research to include comparative biology of related groups of passion vines and their specialist insect associates across geographic regions. This expansion left me asking questions like ‘Do the same plant traits govern community structure of insects in tropical and temperate regions?’ ‘Are passion vine flea beetles and caterpillars more specialized on particular plant functional types in the tropics?’ ‘Are the species of caterpillars and beetles behaving differently across ecosystems characterized by different assemblages of host plants or environmental conditions?’ I love tropical ecology and travelling to Central America to live and work. However, it can be difficult to make these trips regularly because of the time and resources required. Being able to do the same types of studies in Texas where I can get into the field more frequently and for less money ensures that I can stay productive year-round, while seeking answers to questions that can be local or regional in scope.

Living and working in Texas also presents me the opportunity to study the ecology and evolutionary biology of plants and insects that are distributed locally. Since 2019, I have worked with colleagues at BFL on the biology of prickly pear cactus (genus Opuntia) and its specialist insect herbivores. This research was prompted by the arrival of the invasive cactus moth (Cactoblastis cactorum) on the Texas Gulf Coast in Fall 2017.

Field work mentors for the National Science Foundation – Research Experience or Undergraduates (REU) program at La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica in June 2019

Where do you see your research agenda heading here at UT? And how about after?

I want to reflect on the interface between research agendas, experience, and goals. Doing research successfully and sustainably requires qualities difficult to learn in class, but that can come through experience. There are several key characteristics that junior researchers learn on their journeys to fulfilling and productive careers. These include developing one’s ability to gauge situations clearly, a willingness to blend with current events, having the strength to be vulnerable and take risks, and being ready to pivot towards new opportunities when required to, or when they are too valuable to pass up.

Having the space to develop these qualities is often a function of how supportive and respectful one’s major advisor and colleagues are. My research agenda has the full support of my advisor Dr. Larry Gilbert, and my colleagues. My PhD started with a research agenda focused on passion vine flea beetles. This gave my autonomy to explore and develop this system free of competition, and also fit the beetles within the greater research program cultivated by my advisor and former Gilbert Lab members. Very quickly, my field work and desire to frame the passion vine system into a narrative that told the story holistically compelled me to add other aspects to the study system!

Currently, I am collaborating on projects investigating poison dart frog chemistry, how salt affects caterpillar host plant specialization, and global patterns of intraspecific variation in herbivory. All of these systems have different players, but the biological processes involved in governing them are very similar – chemistry, evolutionary ecology, behavior, I love it!

I might keep working on the passion vine system, but cactus research is urgent at this point. I will have to see where the opportunities take me. While a lot is uncertain, and there is much to be done, I am sure that being a scientist is for me and I will do research for the rest of my life.