Korin Rex Jones is one of our 2023 Stengl-Wyer Scholars. Korin is a microbial community ecology researcher fascinated by the role the microbiome can play in health and development across a wide variety of host organisms. He works in the labs of Dr. Nancy Moran and Dr. Jeff Barrick.

As part of the Stengl Wyer Endowment, the Stengl Wyer Postdoctoral Scholars Program provides up to three years of independent support for talented postdoctoral researchers in the broad area of the diversity of life and/or organisms in their natural environments.

In this interview with Korin, he dives into his work on microbiome composition, the untapped potential of further study of host microbiomes, and how the Scholars' Program is enhancing his research.

Tell us where you came from before UT, and what you studied then?

I’m from Virginia Beach and went to Emory and Henry College to pursue a bachelor’s degree. After graduating, I lived in China for five years teaching science courses before moving to Utah where I spent two years working as a medical technologist and volunteering on the side as a fossil preparator and museum STEM lab facilitator while preparing grad school applications. I ended up finding a great lab at Virginia Tech, where I worked on broadening our understanding of community assembly of the amphibian microbiome.

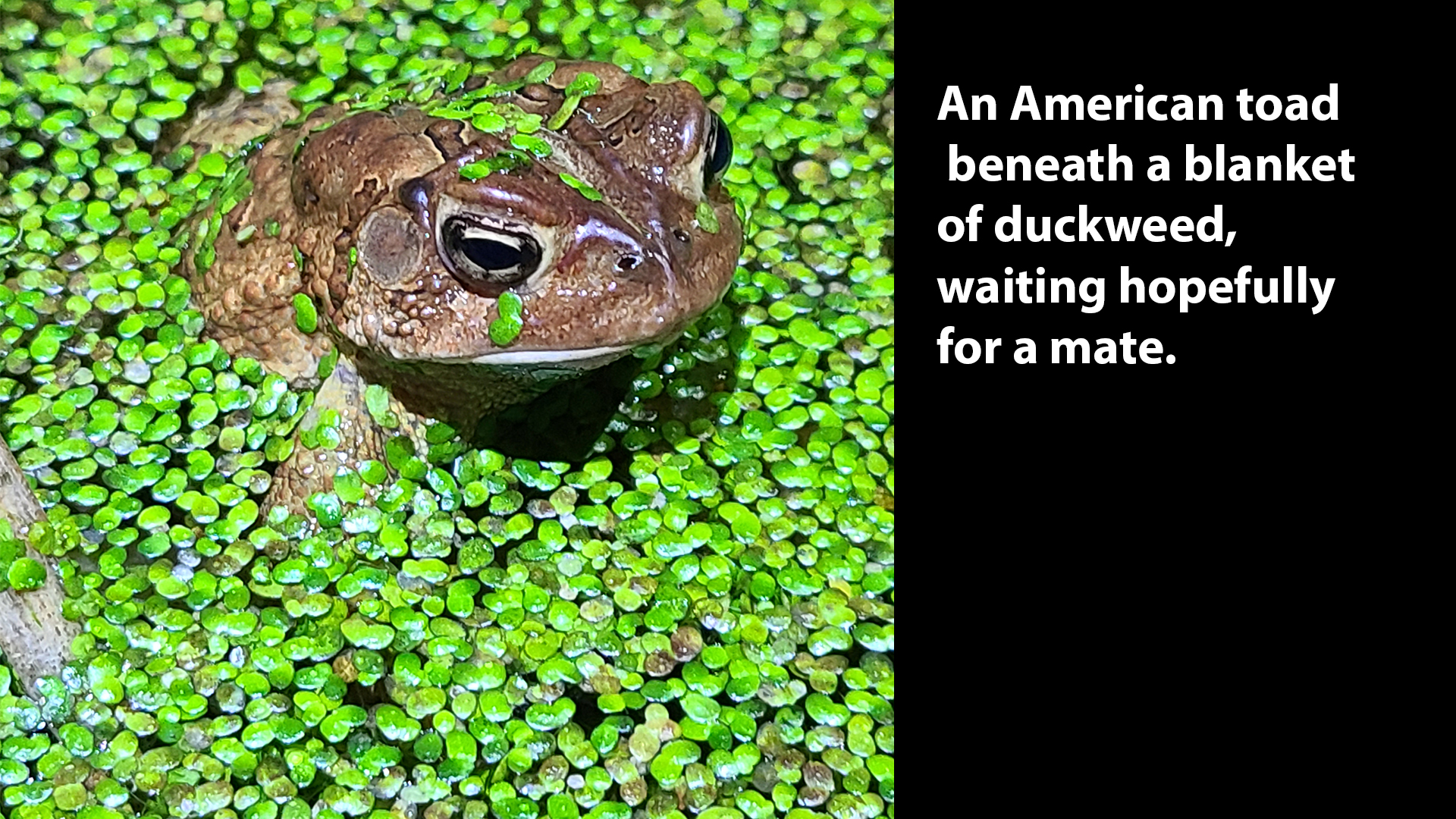

Frog populations are currently experiencing global declines due to an array of different factors. Among these is the presence of the fungal pathogen, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd). Bd is able to infect host frogs through their skin and can ultimately result in death. Whether Bd infection results in mortality differs based on a range of host traits such as health status, species, genetics, and, most interesting to me, microbiome composition. Certain compositions of skin bacteria can inhibit the colonization of Bd and prevent the death of their host frogs. While many researchers agree with the potential of bacteria to prevent lethal infections, we are still working to understand how best to translate this into beneficial microbiome compositions in living hosts.

My PhD research focused on priority effects as one potential way to alter microbiome composition. Briefly, depending on the order in which bacteria colonize a host, we may see increased abundances of those initial colonists later. By inoculating frog eggs with inoculum consisting of singular bacteria strains and providing these initial colonists with a 24-hour advantage before introducing other strains, I was able to increase the relative amount of my initial inoculum. This technique has promise as a method of establishing amphibian microbiomes aimed at preventing Bd infection, however it is still unknown if these changes in relative abundance will be reduced by metamorphosis and the shift from aquatic to terrestrial habitats.

What got you interested in studying the role the microbe plays in health and development?

Microbes (bacteria in particular) are extremely fascinating to me due to their wide range of functional capabilities. Compared to massive multicellular organisms, bacteria are extremely simple life forms, yet they have these extremely varied lifestyles that make their functional capabilities seem endless. There are so many environments that would be certain death to most large organisms where microbes live blissfully. On top of this, host-associated microbes treat their hosts as these massive ecosystems and can dramatically influence how their hosts live and develop. The microbiome may influence host body composition, behavior, disease susceptibility, mating success, and prey acquisition. Despite all the amazing things that the microbiome may do, there are still so many host systems in which almost nothing is known about their associated microbes; meaning that many of these amazing effects on host organisms have yet to be explored.

Does Texas present a unique situation, challenge or benefit for your research?

Texas provides a great opportunity to explore my research questions in both explored and more unexplored systems. Members of the Moran lab have been exploring the microbiome of honeybees and developing effective molecular tools to answer specific questions about honeybee gut bacteria and their relationship with their hosts. In addition to honeybees, both managed and wild, Texas is also home to a myriad of native bee species, of which relatively little is known about their microbiomes. Texas, therefore, can provide me with a system in which to ask detailed questions and also use our understanding of the well-studied honeybees to further our understanding of microbiome assembly and composition in understudied, native bees.

How will being a Stengl-Wyer Scholar help advance your work?

The network of potential collaborators available to me now as a Stengl-Wyer Scholar is extremely enticing. I think one of the coolest aspects of science is learning about the topics that other scientists are passionate about and what drives them to pursue questions in those areas. While not everyone’s research will mesh or combine well with my interests, many of the informal conversations I’ve had over the years have birthed new ideas and new ways of thinking that assist in overcoming boundaries in research.