Living plants need water to survive, but dried museum specimens of plants are exactly the opposite! The Billie L. Turner Plant Resources Center houses more than 1,000,000 such herbarium specimens in the Main Building. This 85+ year-old landmark, also known as the UT Tower, is a central point on the UT campus. Although it originally housed the university’s main library, it also was and is still used today for administrative offices and as the home of the Billie L. Turner Plant Resources Center. In the past, the 16th floor of the Tower held computers that required a supplementary AC unit for special cooling needs. Last September, this ceiling AC unit was found leaking water onto three specimen cabinets. These cabinets are water resistant, but not waterproof. One of them was found with 100% humidity, along with mold-infested specimens in the bottom shelves.

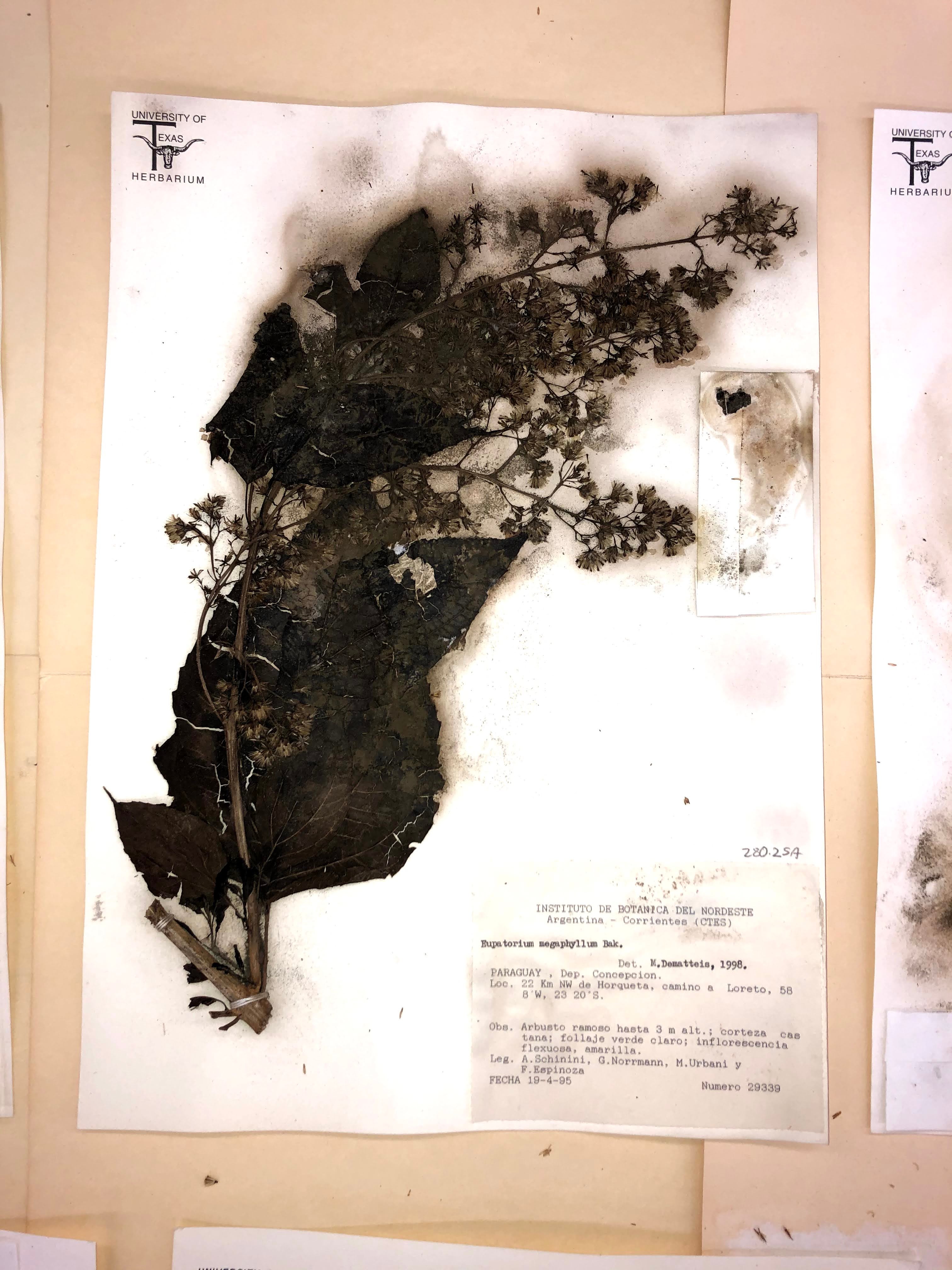

The damaged collection included about 500 specimens in the genus Critonia, a Latin American genus in the sunflower family (Asteraceae), but fortunately only 51 of the specimens had fungi growing on them. Luckily, most of these are represented by duplicate specimens at other institutions. The effort to salvage as many of the moldy specimens here turned out to be complex and surprisingly time-consuming.

The process of saving the cabinet and specimens started by removing the specimens and freezing them to prevent further mold growth. The empty cabinet was sprayed with an antifungal disinfectant. After this, a desiccant was placed inside to remove residual moisture. Then the cabinet was aired out for several weeks to try to alleviate that “mildewy odor.”

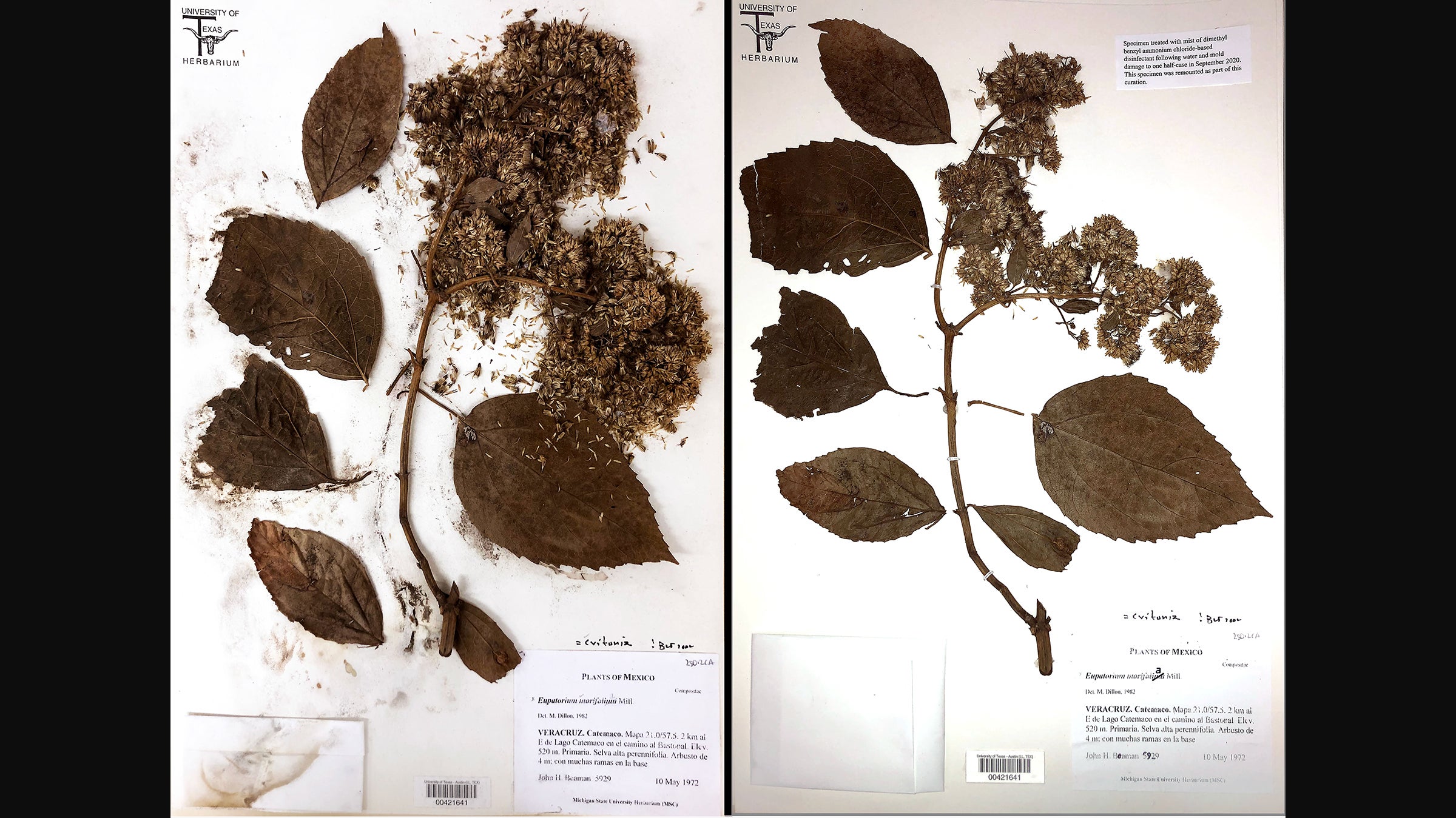

Specimen recovery started with thawing out the sheets and air-drying everything. Those specimens that had only been dampened (but had not sustained mold damage were then refiled. The small group of specimens that required more work to be salvaged were misted with disinfectant to kill fungi and then triaged based on their condition. Those with the most damage were covered with mold that had infiltrated and eaten through the tissue of the specimen and paper. These thirteen specimens had to be discarded. The least-damaged specimens were ones with small amounts of mold that could be removed carefully with a brush and vacuum cleaner. In between these extremes was a group of more than 20 plants with moderate mold on the specimens and paper that required the most intensive restoration. These had to be remounted on clean backing paper, either by carefully removing the specimen from the ruined paper with a blade or by cutting around the specimen and gluing it onto new mounting paper.

The process of salvaging impacted specimens is not perfect—it almost always damages the specimens, which may lose some of its scientific value during the recovery process. Although the ones that must be discarded are irreplaceable, others lose portions of the plant material during the vacuuming and remounting, and some of the material that remains may have become degraded by fungal growth. In this era of declining budgets and staff, the unexpected commitment of time and labor also hurts! Fortunately, this time, only a small part of the overall holdings was affected. Biological resource collections such as the Billie L. Turner Plant Resources Center plan for how to respond to such emergencies, but the hope is never to have to carry out these plans. This particular incident was a scary, small-scale, real-life, proof-of-concept test that the Center’s disaster recovery plan works.

The before and after. Image on left is a water-damaged specimen. Image on right is same specimen cleaned up.